Our Brains Are Built to Learn

Our brains continually goad us to battle the monotonous and predictable, balancing what we know against newness. This drive to disrupt routine is the basis of creativity.

“The Value of Student Variability” (Word Count: 811) (Novak, 2020).

Billions of special cells called neurons transmit information to other neurons so that our brains can help us think and act and recognize danger or reward. Our brains seek and store information ongoingly because “learning is a process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience and increases the potential for improved performance and future learning” (Ambrose et al., 2010). The ways that our brains seek out and transfer stimuli to short-term, working, and long-term memory are different for everybody because from the time we are born, we all gather different stimuli. The series of processes to acquire the stimuli necessary for whatever goal is being pursued depends on that learner’s unique brain. There is also no single way that an individual’s brain will perceive, engage with, or execute a task. The learner increases agency and expertise, not just by exposure to content but by how they seek, connect with, and utilize new stimuli. The learning process is not linear and sensory processing is highly individual. As a result, learners do not have an isolated learning “style” but instead rely on many parts of the brain working together to function within a given context. Despite this evidence, research demonstrates that “belief in the use of learning styles theory is high amongst educators" (Newton, 2020).

"'Neuromyth’ or Helpful Model?” (Word count: 2,460) (Toppo, 2019).

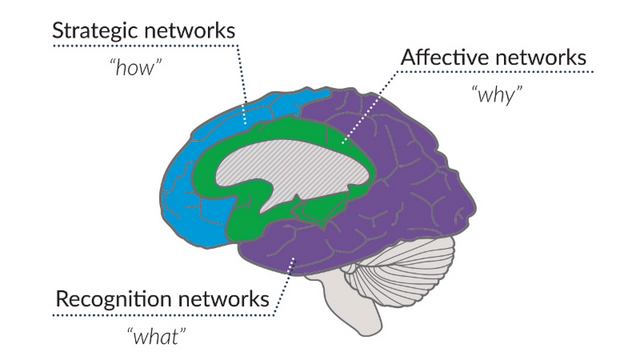

David Rose, a developmental neuropsychologist and educator, co-founded CAST and helped develop the UDL Guidelines. His work was based on the following understanding of how we process information using three primary networks in the brain. These networks can be understood in terms of the three CAST principles.

So let’s look at them a little closer.

Affective networks (GREEN): Affective networks determine the emotional and motivational significance of the world around us. These drive our actions by valuing and prioritizing what we do and learn. The affective networks of the brain correspond to the UDL principle of Engagement.

Recognition networks (PURPLE): Recognition networks align with our seven senses (vision, hearing, taste, smell, touch, balance, and body awareness). These guide the ways that we perceive, build knowledge, and construct meaning of what is represented to us through language, symbols, and images. The recognition networks of the brain correspond to the UDL principle of Representation.

Strategic networks (BLUE): Strategic networks are responsible for executive functioning. This includes cognitive flexibility and the memory operations used to regulate inhibitions, manage complex tasks, and reflect on progress. Strategic networks of the brain correspond to the UDL principle of Action and Expression.

This model for thinking about three broad learning networks can be helpful when we design learning experiences. In subsequent modules, we will further explore these learning networks as we look at each of the UDL principles in depth.

For now, let’s move on to the environmental, social, and attitudinal barriers that may be present in our curriculum and learning environments.