Learner Expertise

The ultimate goal of the UDL framework is to help facilitate the development of learner expertise.

UDL describes the expert learner as one who is:

- purposeful and motivated (Engagement). They can manage themselves when they get stuck, collaborate with others, and focus on a task.

- resourceful and knowledgeable (Representation). They can find and curate information, connect ideas to create new understanding, and transfer knowledge across contexts.

- strategic and goal-directed (Action and Expression). They can break down a task, manage deadlines, organize resources, and communicate critical thinking.

Learning and expertise are not static. They are continual processes that involve practice, adjustment, and refinement. When learners have options to engage, for example, by setting their own goals for how they will learn the required material, or by determining how they will express what they’ve accomplished, they increase their expertise in the process of learning itself.

This video summarizes the ways that learner expertise is an evolving balance between external and internal direction

This video, Expert Learning, provides a great overview of expert learning through a UDL lens.

UDL Expert Learning

>> What does it mean to develop learner expertise? The Center for Applied Special Technology, CAST, defines the expert learner as one who is motivated and purposeful; knowledgeable and resourceful; as well as strategic and goal directed. Let's take a closer look.

Just as we have to work hard to gain expertise in a sport or hobby or in the skills and knowledge of a profession, gaining expertise in learning is no different. Learning how to learn refers to the development of a variety of learning skills whereby the process of learning is not dependent on external direction. At the same time, an expert learner also knows when to seek that external direction if needed. In this sense, an important component of learning expertise is self-reflection. This includes the vulnerability to recognize what we know and don't know; skills we have and don't have; and to seek feedback or external resources. It's not easy to return again and again to being a novice or to expect mistakes in order to learn from them. Identifying the skills and knowledge we need to gain also heightens interest, motivation and persistence, especially when the need is connected to a goal that we aspire to achieve. Aspiration and motivation help us to overcome resistance to personal or professional development and to adopt new approaches. And of course, heightened interest also sparks curiosity, another important component of learner expertise. For example, instead of saying, “this is boring”, the expert learner asks, “what is missing” or “what would make this interesting” or “how is this connected to where I'm heading?” Curiosity leads to critical thinking and critical thinking creates new connections between concepts and helps us to screen new ideas to see if they make sense.

Learning expertise is focused on the learning process regardless of the product or the goal we are striving to achieve. Here are some more fundamentals of learning expertise: spacing new concepts and skills into manageable chunks; self-assessing readiness to know not just how but went to build on those chunks of knowledge and skills; and becoming aware of what works best for each of us in terms of balancing periods of focused concentration with rest and reflection. Learning expertise does not pertain specifically to academic learning or a particular topic; instead, learning expertise increases our willingness to experiment and helps us to scan the horizon for new growth opportunities to be lifelong learners and to envision the world in different ways.

Expert Learning - Runtime 2:51 min

https://youtu.be/VDngj46hZXw

The human brain is already designed to be an expert learner, but barriers can get in the way. The goal is to remove the barriers, so the expert learner emerges – perhaps in a process similar to the popular metaphor for Renaissance artist Michelangelo’s sculpting approach: Chip away at the excess stone until the work of art shines through.

How would you describe your own transformative journey towards expertise as a learner?

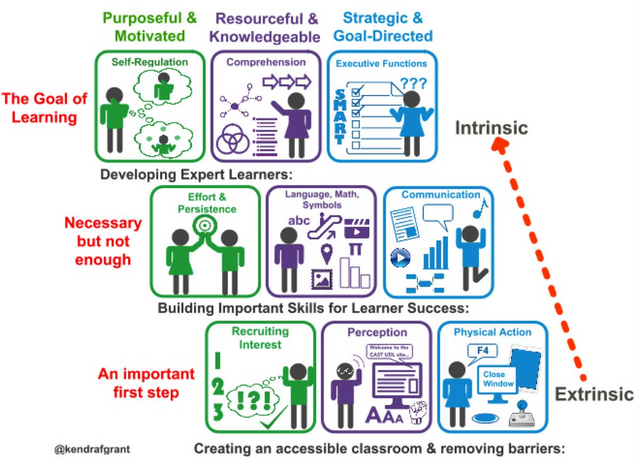

In the following image, Kendra Grant has inverted the UDL chart to explain in detail the processes of moving towards learning expertise:

Beginning at the bottom, “Access” is a foundational step. This means removing barriers that:

- interfere with leaners’ engagement and emotional connection,

- prevent learners from being able to perceive what is represented, and

- restrict learners’ physical access to generate expression.

At this level, the educator takes responsibility for addressing these barriers. They are extrinsic to the learner.

Moving up to “Build,” during this step, educators and learners work together to build strong foundations for success – this involves authentic connections, mastery-oriented feedback, alternatives for interpreting content, strategies to locate resources, and multiple options to practice expressing understanding.

And lastly, learner expertise is increasingly internalized (made intrinsic to the learner) through independent self-reflection and self-direction in determining appropriate materials and strategies, along with ongoing self-assessment and monitoring of developing skills and knowledge and goals. In this way, learning expertise contributes to lifelong learning.

The Future of UDL Guidelines

For curriculum design to proactively provide equitable access for learners across social locations and identities, it must inevitably consider and work to counteract considerable power dynamics in educational spaces. As this course was being piloted, CAST itself began to explore limitations of the UDL framework:

CAST’s work on addressing systemic barriers “Cracks in the Foundation" (Word Count: 1,330).

“At this time of social unrest and disruption, when the inequities and injustices in educational systems (and in cultures more generally) have been highlighted, it is clear that there are many barriers that the UDL framework and its associated guidelines do not explicitly address. Those barriers are quite different than the barriers that are evident in buildings or in classrooms. They are typically institutional or systemic, they are more often about identity than ability, and more often implicit rather than explicit. They are barriers that affect people primarily on who they are rather than what they can do. Those barriers go by many names: racism, genderism, ethnocentrism, and ableism” (Rose, 2021).

Inclusive and equitable learning environments that welcome diversity and difference cannot be achieved without considering and challenging the social and institutional structures that sustain the inequities we seek to dismantle. The next section provides an overview of the frameworks, contexts, and practices that, alongside UDL, are integral to creating true inclusion, accessibility, and community in our learning and teaching practices.