Experiential Learning

Throughout this course, you will have opportunities to reflect on curriculum development and design, delivery methodologies, and assessment strategies as they relate to UDL, equity education, and decolonizing curriculum. You will recognize a number of teaching and learning methods you already employ, but notice that our focus is on online learning. For example, you will see a discussion of technology that moves beyond application to critique. This section reviews some basics around experiential learning, communities of inquiry, the importance of engaging in reflective practice, and strategies to minimize barriers and incorporate new ideas into our teaching practices. These are ideas we will be returning to throughout the course.

The only purpose of education is freedom; the only method is experience.

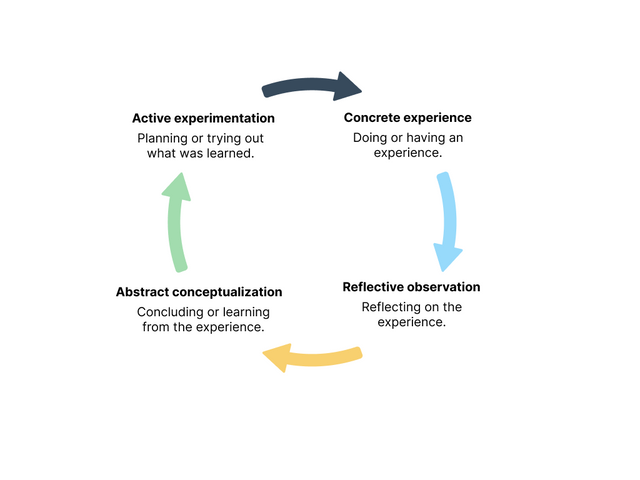

David Kolb’s well-known experiential learning cycle was published in 1984. The cycle counters the idea of a lesson or course as a series of rigid sequential steps. Instead, in its fluidity and repetition, it allows for ongoing reflection as well as a continued shaping of the learning process by learners themselves. Experiential learning offers a valuable pedagogical opportunity to connect with learners’ lived experience and their experience with what is being taught. Learner “engagement” does not just occur at the beginning of a course. Everything the brain takes in is compared to, and connects to, what is already recognizable. In other words, new neural networks build on existing ones as the brain learns by association. The learning cycle – from the why and what to the how of learning – is achieved by connecting our curriculum to the real lives of our learners throughout the learning process. Often misapplied to field or work “experience” (skill application) in postsecondary education, experiential (derived from experience) learning is the foundation of human learning and discovery.

This is why “experience” begins the cycle. From a UDL and neuroscience perspective, a meaningful learning experience starts with educators engaging their learners’ affective systems, which are involved in creating motivation and emotional significance. From an anti-oppression perspective, educators honour their learners’ lived experience and what the learner brings to their learning (derived from experience that may include systemic oppression) at the outset. Without this, their ability to meaningfully participate is compromised.

"Expanding Experiential Learning in Contemporary Adult Education: Embracing Technology, Interdisciplinarity, and Cultural Responsiveness" (Word Count: 5,500).

This is followed by taking time to reflect and communicate about what has been experienced or already derived, in preparation for new learning. From a UDL perspective, this is an opportunity for students to begin to explore goal identification, connections to others, and group norms and responsibilities. From an anti-oppression perspective, this exploration and engagement occur in the context of, and take into account, the socially constructed inequities that are barriers to learning.

Next is conceptualization (content delivery), which from a UDL perspective means offering multiple means for learners to represent their understanding, thereby enhancing their perception and knowledge building. Educators who are using an anti-oppression or decolonizing framework are selecting content that decentres Eurocentric histories and knowledge systems.

And then, experimentation, practice, and application. From a UDL perspective, this means creating multiple options for learners to act and express what they know. Anti-oppressive practice at this stage involves creating a learning environment where meaningful expressions of racialization, Indigenization, queer identity, disability, etc., are celebrated. This will be discussed further in Module 3 when we explore the ways that critical pedagogy intersects with experiential learning.